Anne Ellis Bohannon

Photo From The Independent– Ella Kissi-Debrah (left) pictured with her mother Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah (right). In 2011, 9-year-old Ella died from a asthmatic seizure caused by air pollution. Her mother continues to be an advocate for change surrounding air pollution and it’s health impacts.

In February 2013, 9-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah’s heart stopped when she had an asthmatic seizure. It wasn’t the first time that her asthma had sent her to the hospital, nor the first time she’d gone into cardiac arrest. But this time, the doctors couldn’t save her.

Ella’s autopsy revealed that asthma alone hadn’t prematurely ended her life – the coroner found that she suffered from excessive exposure to particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide, two air pollutants. During the three years of multiple hospitalizations that led up to her death, Ella lived near one of London’s busiest roads, the South Circular. The toxic air coming into her home from the passing vehicles had killed her as surely as if someone had placed her in a running car closed-up in her garage.

Unfortunately, Ella dying because of toxic air isn’t surprising. What’s surprising is that her death is the first known instance of a coroner explicitly attributing someone’s death to air pollution. The scientific community has known for decades the dangers posed by toxic air outdoors and in our homes. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported that about 7 million premature deaths are caused by environmental and household air pollutants annually. Moreover, the WHO has found that 99% of the world’s population breathe an unsafe level of air pollutants.

What are these ubiquitous air pollutants?

Particulate Matter (PM), one of the most prevalent air pollutants and one of two culprit’s in Ella’s death, poses a significant risk to human health. PM refers to tiny solid or liquid particles suspended in the air classified by size: fine particles (PM2.5) and coarse particles (PM10). PM10 includes dust, pollen, and mold and other particles about a 1/7th the size of the average strand of hair. PM2.5 includes combustion particles, organic compounds and metals. They are approximately 1/28th of the size of a human hair. Both can lead to respiratory problems, including asthma, bronchitis, and reduced lung function. PM can also enter the bloodstream and contribute to cardiovascular diseases, such as heart attacks, strokes, and increased blood pressure.

Vehicles and industrial processes emit another notorious air pollutant that contributed to Ella’s death – Nitrogen dioxide (NO2). High levels of NO2 can inflame your airways, worsen respiratory conditions, and increase the susceptibility to respiratory infections.

Studies have also found that other air pollutants Sulfur dioxide (SO2), Carbon monoxide (CO), Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), Ground-level ozone (O3) also have detrimental effects on human health, especially on respiratory and cardiovascular health.

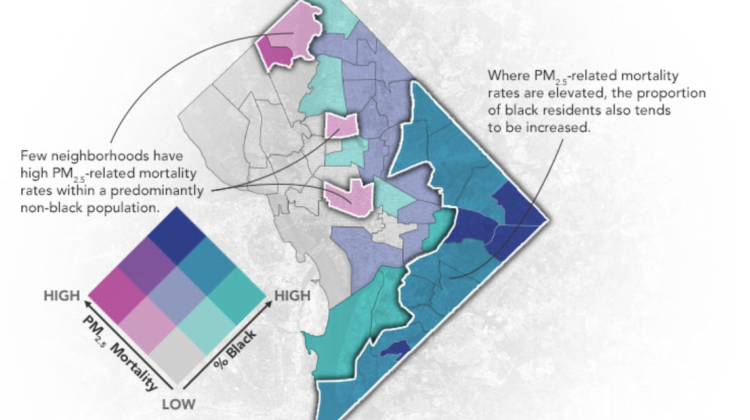

Our home, the greater Washington, DC area, is often used as a prime example of these “silent killers.” In 2021, the study “Estimating intra-urban inequities in PM2.5-attributable health impacts: A case study for Washington, DC,” found that there was a direct correlation between respiratory and cardiovascular deaths and illness caused by PM2.5.

However, the study also addressed a huge underlying problem of air pollution on health: it is not just an environmental issue or a public health issue, but a massive equity issue as well.

The study found that southwest and east DC wards where residents are a much larger percentage of people of color, which disproportionately affected by air-pollutant caused illness. Indeed, the study found that compared to northwest wards with more white people, southwest ward residents were 5 times more likely to have chronic pulmonary disease, lung cancer and stroke, 9 times more likely to have coronary heart disease, had 9 times higher mortality rates, and 30 times more likely to visit the ER for asthma related issues.

Multiple factors contribute to this issue. First and foremost, marginalized communities are more likely to reside in areas with higher pollution levels due to a combination of socioeconomic factors, historical inequities, and discriminatory practices. Industrial facilities, waste treatment plants, and busy transportation corridors tend to be concentrated in these neighborhoods, resulting in increased emissions of harmful pollutants.

Traffic-related pollution poses a significant threat to the health of communities residing near major roadways. The constant stream of vehicles releases nitrogen oxides (NOx), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), all of which contribute to poor air quality. As a consequence, residents in these areas face an elevated risk of respiratory problems, cardiovascular diseases, and other health issues associated with long-term exposure to these pollutants.

Moreover, the lack of green spaces and tree cover in marginalized communities further exacerbates the health inequity. Trees act as natural air filters, helping to mitigate the impact of pollutants and improving air quality. However, low-income neighborhoods often have fewer trees and limited access to parks, robbing residents of the potential health benefits provided by green spaces.

Compounding the issue, individuals in marginalized communities may also face barriers to healthcare access, including limited availability of healthcare facilities, inadequate health insurance coverage, and language barriers. This can result in delayed diagnosis, inadequate treatment, and exacerbated health conditions, further amplifying the health disparities caused by air pollution.

If it’s so bad why aren’t we doing something about toxic air in our lungs and in our lives?

For one, the people most affected are the least likely to know that they are exposed, have awareness about the consequences of their exposure, or be able to do anything about it. That explanation alone, though, suggests that the affluent and powerful aren’t affected, which they are.

Almost 20 years ago, David Foster Wallace famously opened his graduation address at Kenyon College with a story about two fish: “There are these two young fish swimming along, and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’” Wallace was admonishing the graduates to not go through life unconsciously failing to consider what the people around them may be experiencing. His story and argument have a very tangible application in this context. We don’t notice toxic air because we swim in it every day.

Indeed, we struggle with less tangible risks. Despite decades of warnings from scientists about global warming, it took brand-shift to “climate change” and a global rash of highly visible natural disasters to convince the majority of people that we face serious consequences from burning so much fossil fuel. Studies say that toxic air is an epidemic bigger than Covid. But that’s evidence through sterile statistics, not loss of life and billions of dollars from flooded coastal communities and cataclysmic tornadoes. And it’s easy to be skeptical that toxic air is that big of a risk. Afterall, half of the people who smoke die of causes not attributed to their habit of inhaling concentrated toxic air into their lungs several times a day. So how bad can it really be?

Add to that, the other dangers we face that feel so much more urgent. Gun violence, inflation and the cost of living, and anti-LGBTQ+ legislation all seem somehow more pressing. It’s understandable that toxic air doesn’t make our top worry list. But it should, and with significant progress at hand regarding climate change through government and personal action, we have a great opportunity to make progress in reducing the toxicity of the air we swim in every day.

New York has taken the first bold step in our country of addressing climate change and toxic air by banning the burning of fossil fuels in new homes and building starting as early as 2026. Will we follow suit in our nation’s capital and help set an example for others to follow? Will we take steps to protect our most vulnerable neighbors and ourselves in the process.