(2 weeks progression)

“Design, create, and sell functional pottery in collaboration with a local food bank. Learn how to throw on the potter’s wheel to create a variety of functional bowls. During this session, you will use your skills to create artwork and plan an event to benefit partner organizations. “ A group of Field students and their teacher start their intersession Empty bowls – hunger in D.C

By Kennedy Adams

A group of students stood outside the door to their

studio waiting for their teacher to arrive. By the

time Sylvia H(14) got there she’d assumed the door

had been locked. So she did like the rest of them,

she waited, and she waited, and waited. When she

finally tested it though…it opened. A truly

wonderful way to start off a stressful Monday morning.

Sylvia is a newfound member of her school’s

intersession, Bread for the city – hunger in DC. She

started her work Monday Feb 14 at the Field

school: a DC preparatory school located in the old

Cafritz mansion on Foxhill. There’s two ways in, the

school’s entrance from Foxhall road. And a wooded

path down from the field. It leads to 44th street or

reservoir road depending which way you go. The

school is 10 or so acres of land, taken up by 4

buildings, – 3 connected, 1 separate – 2 parking lots, and a field.

She sat with her fellow students, expecting to start

the day with ceramics. Instead the first thing they’re

told to do is write. “we all sat down and we were

given notecards and we got pencils out, and we

were asked to write what we thought of, when we

thought of hunger.” Sylvia recalls. She learned that

empty bowls wasn’t just about the ceramics. The

pots, bowls and plates would go towards

something larger: hunger in DC.

Empty Bowls

kiln is full it will be fired. The glazes on the bowls will melt and color them.

The Empty bowls fundraiser has lived for years as an

international project to fight hunger. It’s meant to be

personalized by whatever artist or community decides

to take up its name. Field took it up as a teaching opportunity.

“I knew I wanted to provide an opportunity to teach

students who do not take 3D art, don’t take ceramics.

If they wanted to try something in the studio I wanted

to give them that opportunity for all students,” Empty

bowls teacher, Sarah Riley explains as part of her

reasons for wanting the intersession. Sarah had

worked on a number of Empty bowls fundraisers

during college at elon in North Carolina “I used to plan

and facilitate an empty bowls…and had a memory of

doing that in college. I thought it might be good for

field students to do something like that”

Sylvia recalled the schedule of her first day while

on a jog. She explained that the group’s time was

split between two activities. In the morning, they

worked on starting and finishing their bowls and

cups. The bowls would be sold at school in an

auction the next week. Day one was an

opportunity for students with no experience to

learn how to do ceramics. More experienced

students like Sylvia got to practice and improve.

“ I’ve been doing ceramics for probably about a

year in total. Half a year doing it in middle school,

and so far this year I’ve been doing it. So that

probably adds up to about a year of experience,

most of which I’ve spent slab building….” she

explained. “And I’ve more recently started working on the wheel”

The School Day starts at 8:30. Most days it led into a

brief get together. Sylvia states that Monday, “after

that warm up we were told it was time to get

straight into making stuff cuz’ we had two weeks and

ceramics takes a while, so we had to get going as

fast as we could.” Ceramic work was a top priority

almost all of week one. The Students would sit down

at the table or at a wheel to prepare themselves.

Whoever’s present in the class went over what

needed to be worked on, and who needed help.

From then on until lunch came work time.

When free time was available the class grouped

together. They’d plan out their auction. It would be a

school-wide event. The students were given free reign

to name and price their bowls however they wanted.

And a partnership had been made with another

intersession group: The History and Chemistry of

Cooking. Many of the bowls would be sold alongside student recipes.

Most days, Sylvia noted, no more than 30 minutes

could be spared on discussions. Friday, Feb 18, was

one day in which time wasn’t a problem. There would

be no volunteer work after lunch. They had the rest of

the day to do as they pleased. Sarah had drawn on

the whiteboard a table naming 5 different groups:

everything that needed to be done for the auction.

Sylvia signed herself up for website development. The

auction would be online. To actually buy anything

they’d need to be a site to bid from. Sylvia Was

partnered with two other students: Julia and Maya.

For the rest of the day, they listed the titles and prices of everyone’s bowls .

Of the other groups, the poster makers sat closest to

the trio. The Bread for the City researchers and

Posters makers had talked about merging. Together,

they’d displayed the class’s research. The posters

would have information on BFC for anyone who

wanted to learn. Everything made would hold

information on BFC and food availability. They’re

promoting their bowls and teaching their mission: killing two birds with one stone.

“So, we are carving these pots and then we’re going

to plan and have a fundraiser where we’re going to

sell these pots to friends and family and anyone

who’s in the field school on friday (feb 25)” Daniel

offered as an explanation of the classes work on

thursday feb 17. Like the other 5 students at a

wheel, he’d been working on trimming one of his

bowls “then we’re going to give the proceeds to

bread for the city. So we do this (ceramics) in the

morning and then in the afternoon we go to bread for the city and volunteer.”

After lunch the students volunteer. Even though they

don’t volunteer every day, they volunteer for the

same group, in the same place every time. The

students are to get on their bus and make their way

to Bread for the City’s southeast location: a 28,132

square foot center at 1700 Good Hope road, 8.2 miles away.

Talking at the table, Sylvia recalls that Field was the

only group there when they arrived. A group of 15

children all getting ready to work. She remembers

that not everyone was doing the same thing.. One

small group was set to triple bag. Sylvia was placed

in that group “I’d been taking bags – two plastic bags

and putting them around paper bags, because we

didn’t want food to just break out of the bags.”

Working on his bowl, Daniel recalled there was a

group of students who put food inside the bags. The

students, he said, placed onions and radishes into

plastic bags. Everything bagged was eventually given to people in need.

(left) students taking away finished bag sets (right)

“So far we’ve been taking cans that get donated and

organizing them into grocery bags which are then

given to people that come around” One student

explained. “people that just walk in no questions

asked, get a grocery bag and take off.” He enjoyed

volunteer work a lot and found BFC’s work very fun.

The students he’s talked to, he said, seemed to like it too.

“It was really great ‘cuz students on Monday went

and bagged a bunch of stuff and then went back on

Tuesday to help again and all of the bags that they

had packed weren’t there anymore so that means

someone got the bag someone used the food” said Sarah.

Bread for the people

Field partnered with Bread for the city in 1995, when 3

students were given internships at the organization. 1996,

another Field student worked with them. Over the last 40

years, Field students have partnered with Bread for the City

a total of 10 times. Empty bowls work now makes that 11.

From their website, Michelle Marshall designs (MMD) image of the Michelle Obama

Southeast Center of Bread for the City. From January to February 2019 MMD was the

architect for Bread for the City’s new Southeast Center. “(We) help Washington, DC residents

living with low income to develop their power to determine the future of their own

communities. We provide food, clothing, medical care, and legal and social services to

reduce the burden of poverty. We seek justice through community organizing and public

advocacy. We work to uproot racism, a major cause of poverty. We are committed to

treating our clients with the dignity and respect that all people deserve.”

According to their website “Bread for the city”

originally existed as two separate organizations in There was its namesake, Bread for the city

made by Emmaus Fellowship. And Zacchaeus Free

Medical Clinic, opened by J. Edward Guinan and

Kathleen Guinan. Zachaeus Free was an outgrowth of

the Community for Creative Non-Violence (CCNV).

Bread for the city lived as the joint project of five neighboring churches.

Both organizations went through major growth

during the 1980’s. The demand for services

continued to rise. Clients grew from less than

1,000 a month to over 3,000. In the 1990’s Bread

for the city opened its first satellite site in

southeast D.C. They distributed food and clothing

from a loaned church basement. Eventually the

two realized it’d be mutually beneficial for them to

combine. They realized that because they worked

close together, shared clients, and were both

outgrowing their properties, they could be

merged. They shared the same goal. They both

wanted to grow. It only made sense to unite. The

shared organization was made official in 1995.

Today Bread for the city offers 6 primary programs

from their two centers in Northwest and

Southeast D.C. They serve an average of 10,000

D.C residents every month. The bread for the city

official website states that their food pantries pack

800-1500 grocery bags a day. Each Filled with food to be delivered to people in need.

Hunger in DC

“Food insecurity is created by a couple major factors.

The first one is availability. It can be really hard to find

healthy nutritious food near you when you live in

what’s called a food desert. And a food desert can be

an area (with)…. no easy access to food.” Hopkins

explained. Starting Friday Feb 18, Empty bowls began

teaching more on the second half of its name – hunger in DC.

“A food desert could be just one mile if you live in a city

with no sidewalks. And so availability is one big factor.

Even if you have stores near you, they may not have

healthy food, that’s still a food desert. If you don’t have

nutritious healthy food” (maybe replace with inflation)

Outside the ceramics room, Sarah had explained that

empty bowls students were encouraged to research

anything they could about food insecurity. Hunger in

DC is right in the name of the intersession. It’s

something that needs to get focused on. And since

ceramics were mostly out of the way it was something

she wanted to be learned about. “the students have

been researching online using their website and

reading testimonies from people who used the

services at bread for the city to try to get some more

information that we can share with the greater Field community.”

currently affected by food insecurity

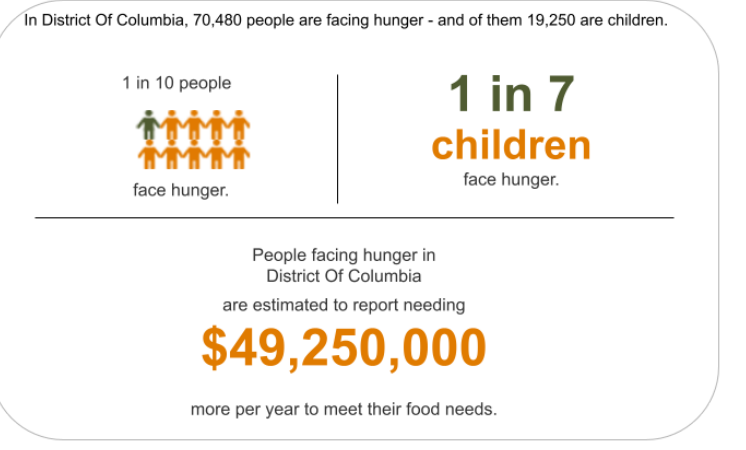

Students learned that 30% of Americans are food

insecure. 1 in 6 Americans don’t have enough to

eat. Citizens in poverty can’t afford to eat healthy

because healthy food is too expensive. And most

‘healthy food’ isn’t really healthy because 70% of

foods made are processed, according to the

documentary, A Place at the Table.

With its auction, Empty bowls will be giving its earnings

to bread for the city to help fund its growth. They’ll be

giving out information on food insecurity to anyone who

wants to learn. Sarah’s artistic vision hopes to have a

broader impact: “[I] wanted to kind of find a way to

authentically connect with a community outside the field

Community but like our neighbors and DC. That’s why

we partnered with bread for the city which is a great

organization that provides a lot of resources to folks

living in DC who are seeking out resources”

Sources used

https://breadforthecity.org/our-history/

https://hunger-report.capitalareafoodbank.org – capital

food bank part 2

https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-

america/district-of-columbia (9)

https://michaelmarshalldesign.com/project/bread-for-

the-city/ (10)

Processed foods make up 70 percent of the US

diethttps://www.marketplace.org › 2013/03/12 ›

processed-fo… (11)

To help/learn more

https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/district-of-columbia

https://www.capitalareafoodbank.org/blog/newsroom

/press-releases/covid-19-has-taken-a-dramatic-toll-

on-the-food-security-of-children-and-latino-families/